Research Highlights

Cutting Colon Cancer Out Properly

Institutions:

University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, University of Milan, Italy

Team:

Rigillo, G., Belluti, S., Campani, V., Ragazzini, G., Ronzio, M., Miserocchi, G., Bighi, B., Cuoghi, L., Mularoni, V., Zappavigna, V., Dolfini, D., Mercatali, L., Alessandrini, A., and Imbriano, C.

Disease Model:

Colon Cancer

Hydrogel:

VitroGel® 3D

A protein that binds DNA and can trigger colorectal cancer apparently comes in two forms: a short form and a long form. It is the latter that is associated with aggressive tumors; if we can coax the splicing of the gene towards the former, we might have a powerful therapeutic tool.

Alternative mRNA splicing is a very important determinant of how a gene functions. If there are multiple exons at a locus for a gene product, the intervening sequences (introns) can be cut out in varying patterns to give longer, shorter, or differentially composed mRNAs, and hence proteins. In the case of the transcription factor NF-Y, which controls the expression of other genes, including oncogenes, how it gets spliced is critical to its downstream function. For NF-Y, a shorter version (NF-Ys) is associated with normal cell growth or benign tumors, while a roughly 28-amino-acid longer version (NF-Yl) is associated with lung, breast, and prostate cancers.

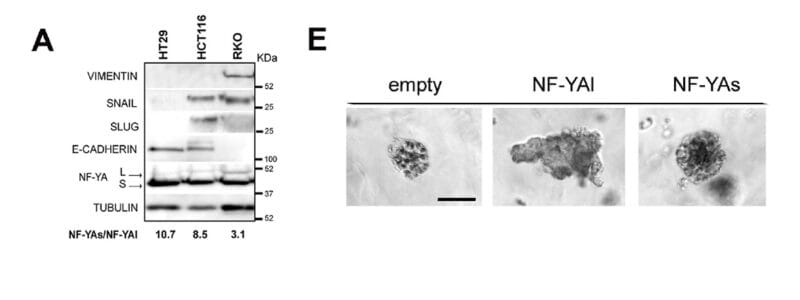

In this study, a team of scientists from Italy examined whether this splicing variation could help explain the aggressiveness of colorectal cancer (CRC) and if there were other environmental correlates to this phenomenon. They compared the clinically reported aggressiveness of CRC in 500 samples deposited online, and, at the same time, genotyped those cells for the two splicing variants and the resulting ratio. There was a significant upregulation of NF-Yl in cell types that were more apt to become cancerous, and overall, a lack of proper splicing regulation in CRC patients. This finding suggested that NF-Y splicing variation could indeed be problematic in sending cells down the malignant pathway in the case of colorectal cancer.

To drill down to a more causative relationship between NF-Y gene splicing variants and cellular phenotype, they cultured cells artificially overexpressing one splicing variant or the other in 2D and 3D conditions and then surveyed those cells for characteristics of aggressive tumor growth. For 3D cell growth in conditions that mimic the biological extracellular matrix (ECM), the researchers grew the cells in TheWell Biosciences’ Vitrogel® 3D hydrogel matrix. Then they were able to compare how well the cells formed colonies when they were anchored to a substrate and compare that to colony formation when they were not anchored to a substrate; this is a key indicator of malignant phenotype. It turned out that cells containing the NF-Yl (longer) splicing variant were less able to form smaller, symmetrical colonies that did those with the NF-Ys variant; those with the longer variant tended to form irregular colonies that were more “cancer-like.”

The authors of this study also undertook several other genotypic and phenotypic comparisons of the cells that overexpressed either the shorter or the longer NF-Y gene products. As a general rule, they found that NF-Y long-bearing cells show changes in the transcription of genes involved in epithelial-mesenchymal transition, extracellular matrix, and cell adhesion … all characteristic of malignancy. They confirmed these findings by xenografting the variants into zebrafish and observing tumor growth.

The sum of the data in this paper implicates the longer NF-Y splicing variant as a causal agent in the progression to malignant CRC. The hope is now that worse CRC outcomes could be predicted more easily with a genetic test, and, more importantly perhaps, that future gene editing techniques can be employed in the fight against colorectal cancer progression.